eSports Leagues and Game Publishers – Monetization Playbook (Pt. 2)

Part 2: eSports Leagues and Game Publishers Monetization Models

Now we move on to the other type of major player in eSports: those who organize the matches. This includes game publishers and independent event organizers / independent leagues.

Unlike traditional sports where annual tournaments are held by a central league like the NHL or NBA, most eSports world championships are held by the game companies themselves. The flow of money goes from fans/players → game developer/publisher → teams and organizations → professional players’ pockets. As such, the larger a game developer/publisher is or the more their fans are willing to spend on the games, the more the entire eSports supply chain benefits as a whole.

(For reference, part 1 is linked here)

eSports Tournaments

From a game developer/publisher’s perspective, large tournaments, especially world championships, serve as fantastic marketing opportunities for the game. Most game developers and publishers follow the below flywheel, which essentially makes tournaments function as huge loss leaders where large annual events draw in new players that eventually convert to paying customers and spend more on the game.

How tournaments get bigger and better

Dota 2’s world championship series, The International, provides interesting insight into how much revenue a tournament can potentially earn. Its annual prize pools reach up to $40 million, the highest of any eSports prize, and this prize pool is algorithmically set to be 25% of all revenues generated in the annual The International-themed battle passes. This suggests that Valve can make $160 million per year in top line from its largest tournament alone.

Other games like Fornite and League of Legends have smaller prize pools but higher playership and viewership, suggesting that their parent companies may make similar amounts of revenue but choose to spend it elsewhere. League of Legends, for example, is known for its visually extravagant Worlds Series championships and well-produced media content.

This is all to say that though some games’ prize pools may not be the largest, the flywheel works, and the marketing from tournaments can generate up to hundreds of millions of dollars in annual revenue.

Tournaments also partner heavily with sponsors. In traditional sports, there are league sponsors and team sponsors. In eSports, in lieu of league sponsors, there are sponsors who support tournament organizers, whether they be game publishers or independent organizers. FTX, for example, signed a 7-year contract with League of Legends’s Championship Series to be its official cryptocurrency exchange in Riot Games’s largest sponsorship agreement to date.

Key Takeaways

- From an independent league’s perspective, tournaments are self-contained profit opportunities where revenue from ticket sales and sponsorships are balanced against the costs of organizing the events.

- From a game publisher’s perspective, ticket sales and sponsorships do represent some nice revenue opportunitites, but I see the greater purpose of tournaments as fantastic marketing opportunities and relevance boosters for the publisher’s games and their related products, physical or digital.

Media Productions

Some game studios/companies make their own content based off of their video game IP. Dota 2’s True Sight documentary series that follows the journey of each year’s The International winners to victory is one great example: each episode garners more than 10 million views, many more than its monthly active players. The parallel to traditional sports here is shows and series like Michael Jordan’s The Last Dance, F1’s Drive to Survive, and Tom Brady’s Man in the Arena, each of which have created buzz, engagement, and new fans in their respective sports.

Another great example is Riot Games’s fantastic utilization of its League of Legends IP in creating a chart topping original animation series (Arcane), a virtual K-Pop group that has close to 1 billion views on YouTube (K/DA), and a series of trailers and music videos for new game updates. Though many of these are elaborate marketing ploys, it is not difficult to envision a business model where videos and TV series based off of gaming and eSports IP are net project value positive endeavors, especially if these game studios have in-house production studios.

While these productions can be seen as marketing tools to increase spending on the main games (similar to the tournaments flywheel), they themselves garner hundreds of millions of views and generate ad revenue on each view. Thus, they can also be seen as revenue engines on their own.

Key Takeaways

- Game studios already create media productions based off of their games’ IP (TV shows featuring game characters) and their eSports scenes (documentaries following a tournament). TV shows have been sold to platforms like Netflix but documentaries have largely been contained on VOD platforms ← slept on opportunity here.

- Media productions by the same companies that make the games (official media productions) easily garner millions of views and appeal to a wider audience than games themselves. They represent great opportunities for ad inserts, in-house marketing (to increase and retain playership), and exclusivity contracts with streaming platforms.

Publishers’ and Organizers’ Merchandising

In eSports, there is a more diverse catalog of products sold directly to consumers than in traditional sports. Most notably, there is a huge market in digital goods sold within the video games themselves. While these do not necessarily all fall under eSports leagues’ revenue streams, digital goods can be seen as complementary products to eSports: more people being engaged with eSports as viewers widens the top-funnel, bringing in more people who later convert to players of the games, who then partially convert to purchasers of digital goods within the games. Conversely, people who play the games themselves (i.e. the bottom funnel) are also more likely to support their favorite professional teams, and people who are willing to spend money on in-game digital goods are likely to be more willing to spend money to support their favorite teams. Furthermore, since the biggest tournament leagues and world championships are held by the game companies themselves, revenue generated from these digital goods sales can be further used to charge the eSports scene.

Physical Merchandise

Like teams, game publishers and event organizers also have their own merch, and they also partner with white label solutions to manufacture them. Some notable examples are Valve’s partnership with We Are Nation to make annually The International-themed jackets, Riot Games’s partnership with Louis Vuitton to make an in-game-skin-inspired real-life clothing line, and NBA 2K’s partnership with Champion to make game uniforms.

Unlike teams, game publishers often have a larger budget to spend on merchandise, allowing them to make more than just clothing lines. Most games sell posters, plushies, figurines, mouse pads, and accessories among others. In some special cases like Nintendo, where the game publisher also produces the game console, themed consoles and accessories can also be considered merch sales.

Digital Goods

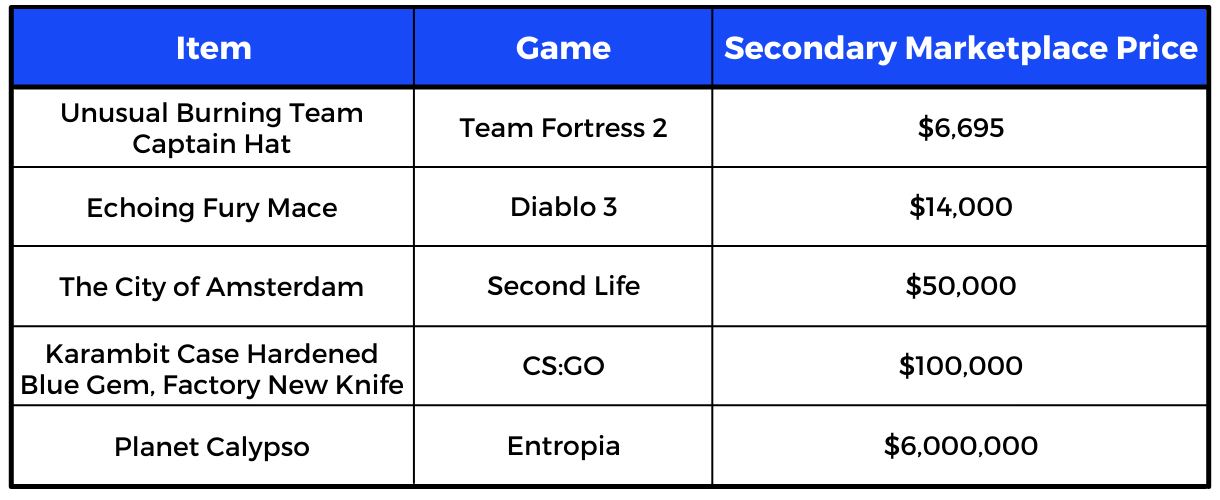

Digital goods in eSports span a number of categories. In games that are more competitive in nature, cosmetics are the most popular. These include skins, hats, sound packs, and other aesthetic alterations to the game that do not affect gameplay mechanics. Cosmetics are wildly popular globally and are most valuable when they are limited edition and sold on a secondary market.

Some crazy expensive in-game goods

Take Valve’s Steam Community Market, for example, on which Valve takes a 20% commission on all transactions. From this marketplace, Valve is able to rake in billions of dollars, a large majority of which comes from digital items that are used in Valve-produced games like CS:GO, Team Fortress 2, and Dota 2. This revenue is then used to produce more games, develop new Steam features and products, as well as organize more eSports events.

While high in transaction value, limited edition item sales are few in quantity. A more recurring source of digital goods revenue for game developers and studios are in the form of battle passes, which are seasonal (roughly annual) bundles of unlockable in-game loot including anything from seasonal cosmetics and virtual in-game currencies to physical merchandise and event passes. Battle passes are typically under $20 and thus quite affordable for most players. Popular games that have battle passes include Apex Legends, various Call of Duty titles, Destiny 2, Dota 2, Fortnite, Halo Infinite, PUBG, Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six Siege, Rocket League, and Valorant.

In addition to battle passes, some game companies are also experimenting with subscription models. Dota 2’s “Dota Plus” ($4/month) and Fornite’s “Crew” ($12/month) give purchasers additional in-game benefits as well as easier access (or even unlocked access) to certain battle pass items.

Key Takeaways

- eSports merchandise from a game publisher’s/league’s perspective includes the physical products that traditional sports are familiar with as well as a whole new set of digital products.

- Revenues earned from merchandise sales charge the tournament flywheel in Part 3.1.

- Innovation happening in eSports digital products is rapid and being replicated in some forms of traditional sports as well.

Overall Key Takeaways for Leagues and Game Publishers

- Game publishers largely generate their eSports revenue through the tournament flywheel outlined above, which is largely a dance between tournament costs and game-related product sales.

- Leagues, on the other hand, approach tournaments as individual profit opportunities which balance arena costs and ticket sales + sponsorships.

- Game publishers supply the games that independent leagues organize tournaments around. Independent leagues boost those games’ off-season relevance and competitive scenes.

To Be Continued…

In the next installment of our reports on the eSports market, we’ll break down:

- Creator Economy Implications

- Web3 Opportunities